Some type 1 diabetes cases in adults misdiagnosed as type 2

Diabetes

"Many might think type 1 diabetes is a "disease of childhood", but research, published in the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, has found it has similar prevalence in adults" BBC News reports

“Doctors 'wrong to assume type 1 diabetes is childhood illness',” says The Guardian.

This follows a study looking at a large number of adults in the UK to see if they had diabetes and if so, which type of the condition they had.

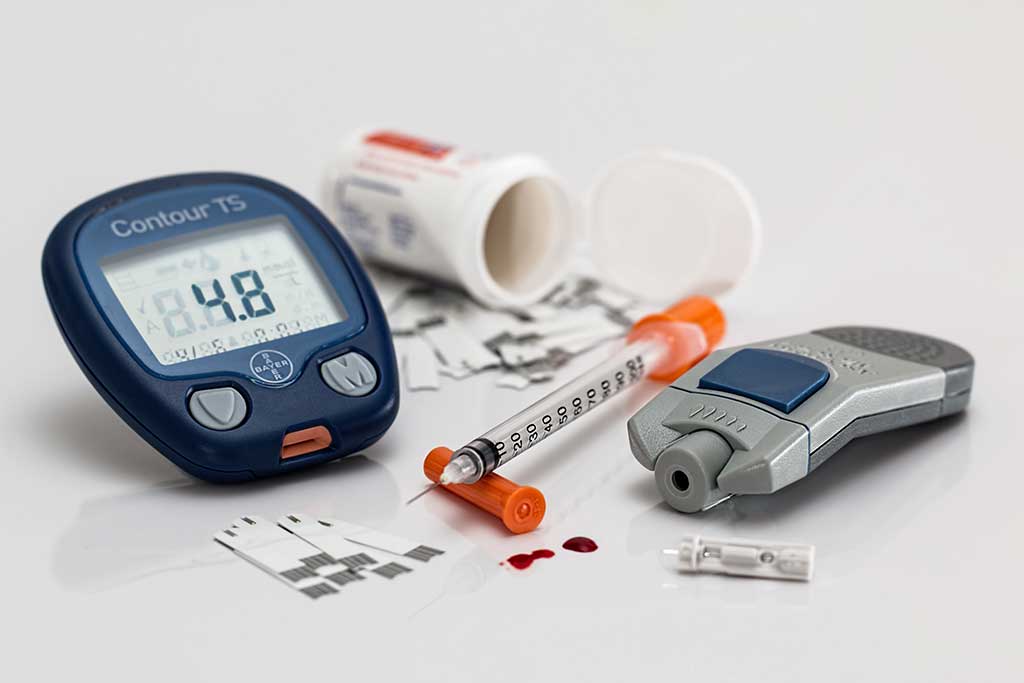

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition where the body destroys the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, so is reliant on life-long insulin injections. Type 2 diabetes is a condition where the person produces limited insulin, or their body can't use it so well. It can be managed in the early stages with changes to diet and medication.

Type 1 diabetes is often thought of as a “childhood illness” as most people are diagnosed at a young age. For this reason, people who develop diabetes as adults are often assumed to have type 2. Perhaps the most famous example is Prime Minister Theresa May who was, at first, misdiagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 2013, when in fact further tests revealed she had type 1.

This study looked at 13,250 people diagnosed with diabetes at a range of ages. Of all people who developed type 1 diabetes, surprisingly 42% were not diagnosed until after the age of 30.

However, only 4% of all newly diagnosed diabetes in the over 30s were type 1. Therefore, although type 1 diabetes starting in adulthood is uncommon, it still highlights the need for healthcare professionals to be aware that not all people who develop diabetes in adulthood automatically have type 2.

Making sure that people receive the correct diagnosis, and therefore the correct treatment, is crucial.

If you have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes but are not responding to treatment, it may be worth discussing the possibility of further testing with your doctor.

Where did the story come from?

The study was carried out by researchers from the University of Exeter using data from a nationwide study called UK Biobank. It was funded by The Wellcome Trust and Diabetes UK. It was published in the peer-reviewed medical journal The Lancet: Diabetes and Endocrinology.

The story was covered by the BBC and The Guardian, both of which accurately covered the key findings and explained the importance of receiving a correct diagnosis to ensure people are given the right treatments.

What kind of research was this?

This researchers used data from a large, ongoing cohort study called UK Biobank which started in 2006. The study aimed to see how people with genes predisposing them to type 1 diabetes developed the condition in later life rather than in childhood or teenage years as usual.

UK Biobank involves more than half a million adults across the country, and has followed them up for a number of years. As well as attending health screening sessions, participants have also given blood samples from which genetic information can be recorded. For this research, a snapshot was taken of people from UK Biobank who were of white European descent, and who had genetic data available.

A cohort study that followed people from childhood throughout their lives may have been able to look at this in more detail. But the size and coverage of the UK Biobank study make this a useful starting point to look at whether people with genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes are diagnosed in adulthood or childhood.

What did the research involve?

The study involved a sample of 379,511 people from the UK Biobank study, of whom a subgroup had diabetes. All were of white European background and had genetic data available. None of the people were related to each other.

The researchers assessed all people for genetic variants known to be associated with type 1 diabetes. They then gave each person a genetic risk score for their risk of developing type 1 diabetes.

Self-reports of a diabetes diagnosis were assessed by questionnaire at study enrolment or later follow-up. People provided information about the age they received a diagnosis, and whether they used insulin within one year of diagnosis (reliance on insulin would indicate type 1). They also reported any hospital admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis (a serious complication of diabetes), and general health such as body mass index.

For the analysis, the researchers compared people with ‘high risk’ or ‘low risk’ for type 1 diabetes based on the results of the risk score. They limited analysis to cases of type 1 or type 2 diabetes occurring in people aged 60 or under at time of diagnosis, as after that point any new cases are almost certain to be type 2 diabetes.

What were the basic results?

In the study sample there were 13,250 people with diabetes, 55% of whom had high genetic risk scores and the remainder had low risk scores.

There were 1,286 cases (9.7%) of type 1 diabetes, and all of these occurred in people with the high risk score:

- 18% of those with a high risk score were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, the remainder with type 2

- 42% of those in the high risk group diagnosed with type 1 (537) were diagnosed between the ages of 31 and 60, with the remainder diagnosed under the age of 30 (as is more usual)

- of all people aged under 30 at time of diabetes diagnosis (all risk categories), 74% had type 1 diabetes

- of all people aged 31 to 60 at time of diabetes diagnosis, 4% had type 1 diabetes

- across all ages of life, people with a high genetic risk score were more likely to be diagnosed with any type of diabetes than people with a low risk score

All people diagnosed with type 1 after the age of 30 needed insulin treatment, compared to only 16% of people diagnosed with type 2 (who started insulin later, after 7 years on average). They also had a lower body mass index (BMI) than those with type 2.

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers stated their findings have “clear clinical implications”, alerting healthcare professionals to the fact that type 1 diabetes can occur in the over-30s. They recommend that recognition of late-onset type 1 diabetes is an important area of improvement for both medicine and research.

Conclusion

This study gives us an important insight into the way in which type 1 diabetes has been mislabelled as a “childhood condition”. It suggests that a number of people with genetic risk factors are also diagnosed in midlife, when most new diabetes diagnoses would be thought to be type 2.

However, there are a few points to note:

- The study shows that of all people diagnosed with diabetes after age 30, the vast majority (96%) were still type 2 diagnoses. Therefore, though practitioners need to be aware, this only accounts for a small proportion of all diagnoses.

- Even among people with hereditary risk factors for type 1 diabetes, most diagnoses were still type 2.

- The diagnosis of diabetes was based on people's own reports, rather than looking at medical records. People are unlikely to be wrong about whether they have the condition or not, but there may be some uncertainty as to whether they self-reported the correct type, age at which they were diagnosed, or when they started insulin.

- The study only looked at people from a white European background. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes prevalence and risk factors may differ in people from other ethnic backgrounds, so this study’s results cannot be generalised to everyone.

- When the UK Biobank study started in 2006, the majority of people taking part were aged 40 or over. This means that they were children in the 1980s or earlier. Since that time, the diagnosis of diabetes may have improved. It would also mean that people who suffered complications from the disease and died in earlier life would not have been included.

- The study can't tell us how many of these people with type 1 in later life may have been misdiagnosed initially, or had insulin treatment delayed when they needed this to start with.

- People who commit to take part in studies like UK Biobank might be more active about monitoring and managing their health than people in the general population. Therefore people in this study may have had slightly different experiences when getting diagnoses, or have different lifestyle behaviours that could affect their risk of conditions like diabetes.

Nonetheless, this study highlights the fact that type 1 diabetes can begin in adulthood as well as in childhood. Adults diagnosed with diabetes must receive the correct diagnosis to get the right treatment as soon as possible. If you are concerned that you may have been misdiagnosed, ask the doctor in charge of your care for advice.

Subscribe

Subscribe Ask the doctor

Ask the doctor Rate this article

Rate this article Find products

Find products