'Radical' low-calorie diet may help reverse type 2 diabetes

Diabetes

"Radical diet can reverse type 2 diabetes," The Guardian reports

"Radical diet can reverse type 2 diabetes," reports The Guardian.

This follows a trial of an intensive weight loss programme for overweight and obese people with type 2 diabetes, conducted at GP surgeries in Scotland and Tyneside. People were randomised to follow either the Counterweight Plus weight loss programme or standard care for 12 months.

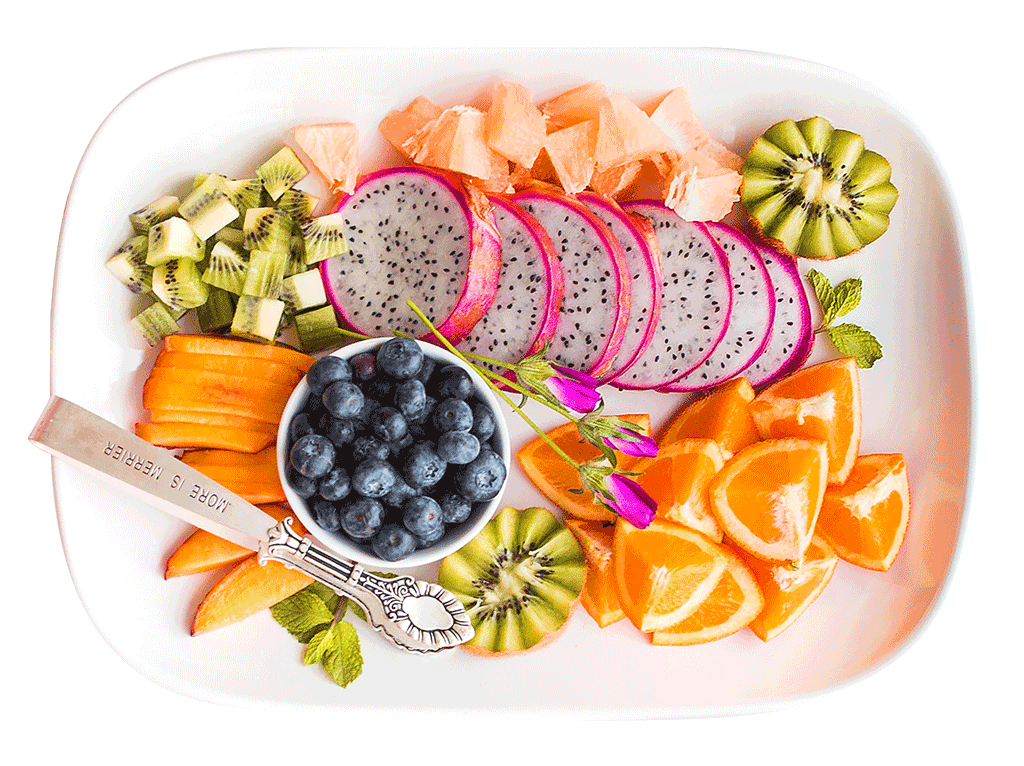

Counterweight Plus is a low-calorie diet plan that involves an initial phase of consuming around 850 calories a day for 3 to 5 months. This is followed by a 2- to 8-week period where calorie intake is slowly increased. Participants are then encouraged to attend monthly advice meetings, with the aim of maintaining their weight loss.

People on the Counterweight Plan lost 10kg on average, with around a quarter achieving the target of losing 15kg or more. Half went into diabetes remission – defined as normal blood glucose control – compared with only a handful in the standard care group.

The dietary approach definitely shows promise, but there are several reasons to be cautious at this stage. This sort of intensive calorie restriction wouldn't be suitable for everyone and should only be conducted under careful medical supervision. One person also developed severe abdominal pain, related to gallstones, thought to be caused by the intervention. The diet needs further study to ensure it's safe and suitable for widespread adoption.

If you have diabetes, you shouldn't make radical changes to your diet for now, or any changes to your diabetes medication, without consulting your doctor.

Where did the study come from?

The study was conducted by researchers from several institutions in the UK, including the University of Glasgow and Newcastle University. Funding was provided by Diabetes UK. The study was published in the peer-reviewed medical journal The Lancet.

The Guardian's and BBC News' reporting of the study was accurate. Both included an interview with a woman who took part in the study.

What kind of research was this?

This was a randomised controlled trial, carried out in general practices, investigating whether intensive weight loss followed by weight management could prompt remission of type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is estimated to affect 1 in 10 adults in the UK. It's known to be linked to weight gain in adult life, possibly because of excess fat build-up in the liver and pancreas. Previous studies have suggested that a restricted-calorie diet may release insulin from the pancreas and lead to better blood glucose control.

However, as none of these studies looked at long-term effects, this trial looked at the effects of the diet over the course of a year. It was a cluster randomised trial, meaning that randomisation was done by GP catchment area rather than on an individual-participant basis.

What did the research involve?

The trial, called DiRECT (Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial), was carried out at 49 general practices in Scotland and Tyneside. Eligible participants were adults (aged 20 to 65) who had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and had a body mass index (BMI) signifying they were overweight or obese (27 to 45kg/m2).

Various groups were excluded, including those needing to take insulin, people with very poor glucose control, people with kidney failure and those taking weight loss drugs.

Practices were randomised to the weight management programme (Counterweight Plus) or to the control of standard best practice care.

In the intervention practices, nurses were given training in the Counterweight Plus programme.

The programme was split into three phases:

- Three months of total diet replacement using a low-energy-formula diet (825 to 853kcal a day; 59% carbohydrate, 13% fat, 26% protein, 2% fibre). To put this in context, the recommended calorie intake for healthy adults is 2,000kcal a day for women and 2,500kcal a day for men. This phase could be extended to 5 months if the person wanted.

- Between 2 and 8 weeks of structured food reintroduction (50% carbohydrate, 35% fat, 15% protein).

- An ongoing structured programme with monthly meetings for weight loss maintenance.

For people in the intervention group, diabetes and blood pressure drugs were stopped on the first day of the weight loss programme, but blood glucose and blood pressure were regularly monitored so they could be reintroduced if needed.

People were asked to maintain their typical levels of physical activity during the diet replacement phase but to not do any more than normal. During food reintroduction, they were given step counters and asked to do 15,000 steps a day. They also wore wrist monitors over 7-day periods to track physical activity and sleep.

The main outcomes of interest were weight loss of 15kg or more and remission of diabetes after at least two months of no diabetes medications.

Diabetes remission was assessed by looking at glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), which gives an overall indication of blood glucose control over the past few months. They looked for levels below 6.5% (or 45mmol/mol), which is the usual threshold for diabetes diagnosis. The total follow-up period was 12 months.

A total of 306 people were included across the 49 practices. The study was open-label, meaning all participants and researchers were aware of group assignment.

What were the basic results?

By 12 months, 15 people (24%) in the diet group had lost 15kg or more – no one in the control group achieved this.

On average, body weight fell by 1kg among controls and just under 10kg in the intervention group (-8.8kg, 95% confidence interval [CI] -10.3 to -7.3).

Similar patterns were seen for BMI change. The tendency was for nearly all the weight to be lost during the total diet replacement phase, followed by small gains of 1 to 2kg during the subsequent phases.

Diabetes remission (HbA1c below 6.5%) was achieved by 46% of the diet group and 4% of the control group. On average, HbA1c fell by 0.9% in the diet group and increased by 0.1% in the control group (difference -0.85%, 95% CI -1.10 to -0.59). Remission only occurred among people who lost weight – 86% of those who lost 15kg achieved remission.

By 12 months, 74% of those in the diet group were not taking any diabetes medication, compared with only 18% in the control group.

One person in the diet group experienced serious adverse effects of abdominal pain and biliary colic. This was thought to be a result of the intervention.

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers said: "Our findings show that, at 12 months, almost half of participants achieved remission to a non-diabetic state and off antidiabetic drugs."

Because of this, they suggested that remission of type 2 diabetes is "a practical target for primary care".

Conclusion

This is a promising trial that suggests an intensive calorie-restriction programme, followed by reintroduction of a more normal diet and steps to keep weight off, can lead to weight loss and remission of type 2 diabetes.

This was a well-designed trial that had many strengths, such as analysing all participants in their assigned group regardless of whether they completed the study (although very few were lost to follow-up) and ensuring they included enough participants to be able to reliably detect differences between them.

The nature of the intervention meant it wasn't possible for people to be unaware of group assignment but, because weight and HbA1c are objective measures, the risk of bias was minimised.

There are some points to be aware of, however:

- Most people in this trial were obese, with an average BMI of 35. Therefore, we shouldn't assume that intensive weight loss and calorie restriction are appropriate for all people with diabetes.

- The participants had raised HbA1c, but the average level was around 7.5%, so their blood glucose control wasn't as bad as it could be. The researchers also excluded people who had needed to start taking insulin. So, again, discontinuing all medication and managing diabetes by weight loss alone likely wouldn't be appropriate for everyone.

- This isn't the sort of diet you could undertake yourself. Intensive calorie restriction and energy balance is something that would need to be carefully monitored by health practitioners, especially if you have type 2 diabetes.

- Although only one person had serious adverse effects related to the intervention, further investigation is needed to be sure that these, and other side effects, don't occur more regularly in larger groups.

- The 12-month follow-up was a positive aspect of the study, but the participants will still need to be tracked to see how their diabetes and weight progress in the coming years.

- Because the participants were predominantly of white ethnicity, it's unclear whether the approach would be suitable for other groups – for example, for people from an Asian background, who have a higher risk of diabetes.

This intervention definitely shows promise, but further research is needed. For now, if you have type 2 diabetes, you shouldn't undertake any treatment changes or intensive weight loss without medical support.

Subscribe

Subscribe Ask the doctor

Ask the doctor Rate this article

Rate this article Find products

Find products